In 1924, André Breton published the Manifesto of Surrealism, initiating one of the essential art movements of 20th century – the Surrealism. Although the art movement had its end in the sixties of 20th century, Surrealism survived because some essentials became a genetic code of contemporary art.

Manifesto of Surrealism

(André Breton 1924 )

So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life – real life, I mean – that in the end this belief is lost. Man, that inveterate dreamer, daily more discontent with his destiny, has trouble assessing the objects he has been led to use, objects that his nonchalance has brought his way, or that he has earned through his own efforts, almost always through his own efforts, for he has agreed to work, at least he has not refused to try his luck (or what he calls his luck!). At this point he feels extremely modest: he knows what women he has had, what silly affairs he has been involved in; he is unimpressed by his wealth or his poverty, in this respect he is still a newborn babe and, as for the approval of his conscience, I confess that he does very nicely without it. If he still retains a certain lucidity, all he can do is turn back toward his childhood which, however his guides and mentors may have botched it, still strikes him as somehow charming. There, the absence of any known restrictions allows him the perspective of several lives lived at once; this illusion becomes firmly rooted within him; now he is only interested in the fleeting, the extreme facility of everything. Children set off each day without a worry in the world. Everything is near at hand, the worst material conditions are fine. The woods are white or black, one will never sleep.

But it is true that we would not dare venture so far, it is not merely a question of distance. Threat is piled upon threat, one yields, abandons a portion of the terrain to be conquered. This imagination which knows no bounds is henceforth allowed to be exercised only in strict accordance with the laws of an arbitrary utility; it is incapable of assuming this inferior role for very long and, in the vicinity of the twentieth year, generally prefers to abandon man to his lusterless fate.

Though he may later try to pull himself together on occasion, having felt that he is losing by slow degrees all reason for living, incapable as he has become of being able to rise to some exceptional

situation such as love, he will hardly succeed. This is because he henceforth belongs body and soul to an imperative practical necessity which demands his constant attention. None of his gestures will be expansive, none of his ideas generous or far-reaching. In his mind’s eye, events real or imagined will be seen only as they relate to a welter of similar events, events in which he has not participated, abortive events. What am I saying: he will judge them in relationship to one of these events whose consequences are more reassuring than the others. On no account will he view them as his salvation.

Beloved imagination, what I most like in you is your unsparing quality.

There remains madness, “the madness that one locks up,” as it has aptly been described. That madness or another…. We all know, in fact, that the insane owe their incarceration to a tiny number of

legally reprehensible acts and that, were it not for these acts their freedom (or what we see as their freedom) would not be threatened. I am willing to admit that they are, to some degree, victims of their imagination, in that it induces them not to pay attention to certain rules – outside of which the species feels threatened – which we are all supposed to know and respect. But their profound indifference to the way in which we judge them, and even to the various punishments meted out to them, allows us to suppose that they derive a great deal of comfort and consolation from their imagination, that they enjoy their madness sufficiently to endure the thought that its validity does not extend beyond themselves. And, indeed, hallucinations, illusions, etc., are not a source of trifling pleasure. […]

The case against the realistic attitude demands to be examined, following the case against the materialistic attitude. The latter, more poetic in fact than the former, admittedly implies on the part of man a kind of monstrous pride which, admittedly, is monstrous, but not a new and more complete decay. It should above all be viewed as a welcome reaction against certain ridiculous tendencies of spiritualism. Finally, it is not incompatible with a certain nobility of thought. By contrast, the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit. It is this attitude which today gives birth to these ridiculous books, these insulting plays. It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog’s life. The activity of the best minds feels the effects of it; the law of the lowest common denominator finally prevails upon them as it does upon the others. [. . .]

We are still living under the reign of logic: this, of course, is what I have been driving at. But in this day and age logical methods are applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest. The absolute rationalism that is still in vogue allows us to consider only facts relating directly to our experience. Logical ends, on the contrary, escape us. It is pointless to add that experience itself has founditself increasingly circumscribed. It paces back and forth in a cage from which it is more and more difficult to make it emerge. It too leans for support on what is most immediately expedient, and it is protected by the sentinels of common sense. Under the pretense of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices. It was, apparently, by pure chance that a part of our mental world which we pretended not to be concerned with any longer — and, in my opinion by far the most important part — has been brought back to light. For this we must give thanks to the discoveries of Sigmund Freud. On the basis of these discoveries a current of opinion is finally forming by means of which the human explorer will be able to carry his investigation much further, authorized as he will henceforth be not to confine himself solely to the most summary realities. The imagination is perhaps on the point of reasserting itself, of reclaiming its rights. If the depths of our mind contain within it strange forces capable of augmenting those on the surface, or of waging a victorious battle against them, there is every reason to seize them — first to seize them, then, if need be, to submit them to the control of our reason. The analysts themselves have everything to gain by it. But it is worth noting that no means has been designated a priori for carrying out this undertaking, that until further notice it can be construed to be the province of poets as well as scholars, and that its success is not dependent upon the more or less capricious paths that will be followed.

Freud very rightly brought his critical faculties to bear upon the dream. It is, in fact, inadmissible that this considerable portion of psychic activity (since, at least from man’s birth until his death, thought offers no solution of continuity, the sum of the moments of the dream, from the point of view of time, and taking into consideration only the time of pure dreaming, that is the dreams of sleep, is not inferior to the sum of the moments of reality, or, to be more precisely limiting, the moments of waking) has still today been so grossly neglected. I have always been amazed at the way an ordinary observer lends so much more credence and attaches so much more importance to waking events than to those occurring in dreams. It is because man, when he ceases to sleep, is above all the plaything of his memory, and in its normal state memory takes pleasure in weakly retracing for him the circumstances of the dream, in stripping it of any real importance, and in dismissing the only determinant from the point where he thinks he has left it a few hours before: this firm hope, this concern. He is under the impression of continuing something that is worthwhile. Thus the dream finds itself reduced to a mere parenthesis, as is the night.

And, like the night, dreams generally contribute little to furthering our understanding. This curious state of affairs seems to me to call for certain reflections:

1) Within the limits where they operate (or are thought to operate) dreams give every evidence of being continuous and show signs of organization. Memory alone arrogates to itself the right to excerpt from dreams, to ignore the transitions, and to depict for us rather a series of dreams than the dream itself.

By the same token, at any given moment we have only a distinct notion of realities, the coordination of which is a question of will.* (Account must be taken of the depth of the dream. For the most part I retain only what I can glean from its most superficial layers. What I most enjoy contemplating about a dream is everything that sinks back below the surface in a waking state, everything I have forgotten about my activities in the course of the preceding day, dark foliage, stupid branches. In “reality,” likewise, I prefer to fall.) What is worth noting is that nothing allows us to presuppose a greater dissipation of the elements of which the dream is constituted. I am sorry to have to speak about it according to a formula which in principle excludes the dream. When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers? I would like to sleep, in order to surrender myself to the dreamers, the way I surrender myself to those who read me with eyes wide open; in order to stop imposing, in this realm, the conscious rhythm of my thought.

Perhaps my dream last night follows that of the night before, and will be continued the next night, with an exemplary strictness. It’s quite possible, as the saying goes. And since it has not been proved in the slightest that, in doing so, the “reality” with which I am kept busy continues to exist in the state of dream, that it does not sink back down into the immemorial, why should I not grant to dreams what I occasionally refuse reality, that is, this value of certainty in itself which, in its own time, is not open to my repudiation? Why should I not expect from the sign of the dream more than I expect from a degree of consciousness which is daily more acute? Can’t the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life? Are these questions the same in one case as in the other and, in the dream, do these questions already exist? Is the dream any less restrictive or punitive than the rest? I am growing old and, more than that reality to which I believe I subject myself, it is perhaps the dream, the difference with which I treat the dream, which makes me grow old.

2) Let me come back again to the waking state. I have no choice but to consider it a phenomenon of interference. Not only does the mind display, in this state, a strange tendency to lose its bearings (as evidenced by the slips and mistakes the secrets of which are just beginning to be revealed to us), but, what is more, it does not appear that, when the mind is functioning normally, it really responds to anything but the suggestions which come to it from the depths of that dark night to which I commend it. However conditioned it may be, its balance is relative. It scarcely dares express itself and, if it does, it confines itself to verifying that such and such an idea, or such and such a woman, has made an impression on it.

What impression it would be hard pressed to say, by which it reveals the degree of its subjectivity, and nothing more. This idea, this woman, disturb it, they tend to make it less severe. What they do is isolate the mind for a second from its solvent and spirit it to heaven, as the beautiful precipitate it can be, that it is. When all else fails, it then calls upon chance, a divinity even more obscure than the others to whom it ascribes all its aberrations. Who can say to me that the angle by which that idea which affects it is offered, that what it likes in the eye of that woman is not precisely what links it to its dream, binds it to those fundamental facts which, through its own fault, it has lost? And if things were different, what might it be capable of? I would like to provide it with the key to this corridor.

3) The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonizing question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart’s content. And if you

should die, are you not certain of reawaking among the dead? Let yourself be carried along, events will not tolerate your interference. You are nameless. The ease of everything is priceless.

What reason, I ask, a reason so much vaster than the other, makes dreams seem so natural and allows me to welcome unreservedly a welter of episodes so strange that they could confound me now as I

write? And yet I can believe my eyes, my ears; this great day has arrived, this beast has spoken.

If man’s awaking is harder, if it breaks the spell too abruptly, it is because he has been led to make for himself too impoverished a notion of atonement.

4) From the moment when it is subjected to a methodical examination, when, by means yet to be determined, we succeed in recording the contents of dreams in their entirety (and that presupposes a

discipline of memory spanning generations; but let us nonetheless begin by noting the most salient facts), when its graph will expand with unparalleled volume and regularity, we may hope that the mysteries which really are not will give way to the great Mystery. I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak. It is in quest of this surreality that I am going, certain not to find it but too unmindful of my death not to calculate to some slight degree the joys of its possession.

A story is told according to which Saint-Pol-Roux, in times gone by, used to have a notice posted on the door of his manor house in Camaret, every evening before he went to sleep, which read: THE

POET IS WORKING.

A great deal more could be said, but in passing I merely wanted to touch upon a subject which in itself would require a very long and much more detailed discussion; I shall come back to it. At this

juncture, my intention was merely to mark a point by noting the hate of the marvelous which rages in certain men, this absurdity beneath which they try to bury it. Let us not mince words: the marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful. [. . .]

One evening, therefore, before I fell asleep, I perceived, so clearly articulated that it was impossible to change a word, but nonetheless removed from the sound of any voice, a rather strange

phrase which came to me without any apparent relationship to the events in which, my consciousness agrees, I was then involved, a phrase which seemed to me insistent, a phrase, if I may be so bold, which was knocking at the window. I took cursory note of it and prepared to move on when its organic character caught my attention. Actually, this phrase astonished me: unfortunately I cannot remember it exactly, but it was something like: “There is a man cut in two by the window,” but there could be no question of ambiguity, accompanied as it was by the faint visual image* (Were I a painter, this visual depiction would doubtless have become more important for me than the other. It was most certainly my previous predispositions which decided the matter. Since that day, I have had occasion to concentrate my attention voluntarily on similar apparitions, and I know they are fully as clear as auditory phenomena. With a pencil and white sheet of paper to hand, I could easily trace their outlines. Here again it is not a matter of drawing, but simply of tracing. I could thus depict a tree, a wave, a musical instrument, all manner of things of which I am presently incapable of providing even the roughest sketch. I would plunge into it, convinced that I would find my way again, in a maze of lines which at first glance would seem to be going nowhere. And, upon opening my eyes, I would get the very strong impression of something “never seen.” The proof of what I am saying has been provided many times by Robert Desnos: to be convinced, one has only to leaf through the pages of issue number 36 of Feuilles libres which contains several of his drawings (Romeo and Juliet, A Man Died This Morning, etc.) which were taken by this magazine as the drawings of a madman and published as such.) of a man walking cut half way up by a window perpendicular to the axis of his body. Beyond the slightest shadow of a doubt, what I saw was the simple reconstruction in space of a man leaning out a window. But this window having shifted with the man, I realized that I was dealing with an image of a fairly rare sort, and all I could think of was to incorporate it into my material for poetic construction. No sooner had I granted it this capacity than it was in fact succeeded by a whole series of phrases, with only brief pauses between them, which surprised me only

slightly less and left me with the impression of their being so gratuitous that the control I had then exercised upon myself seemed to me illusory and all I could think of was putting an end to the

interminable quarrel raging within me. [. . .]

Completely occupied as I still was with Freud at that time, and familiar as I was with his methods of examination which I had some slight occasion to use on some patients during the war, I resolved to obtain from myself what we were trying to obtain from them, namely, a monologue spoken as rapidly as possible without any intervention on the part of the critical faculties, a monologue consequently unencumbered by the slightest inhibition and which was, as closely as possible, akin to spoken thought. It had seemed to me, and still does — the way in which the phrase about the man cut in two had come to me is an indication of it — that the speed of thought is no greater than the speed of speech, and that thought does not necessarily defy language, nor even the fast-moving pen. It was in this frame of mind that Philippe Soupault — to whom I had confided these initial conclusions – and I decided to blacken some paper, with a praiseworthy disdain for what might result from a literary point of view. The ease of execution did the rest. By the end of the first day we were able to read to ourselves some fifty or so pages obtained in this manner, and begin to compare our results. All in all, Soupault’s pages and mine proved to be remarkably similar: the same overconstruction, shortcomings of a similar nature, but also, on both our parts, the illusion of an extraordinary verve, a great deal of emotion, a considerable choice of images of a quality such that we would not have been capable of preparing a single one in longhand, a very special picturesque quality and, here and there, a strong comical effect. The only difference between our two texts seemed to me to derive essentially from our respective tempers. Soupault’s being less static than

mine, and, if he does not mind my offering this one slight criticism, from the fact that he had made the error of putting a few words by way of titles at the top of certain pages, I suppose in a spirit of mystification. On the other hand, I must give credit where credit is due and say that he constantly and vigorously opposed any effort to retouch or correct, however slightly, any passage of this kind which seemed to me unfortunate. In this he was, to be sure, absolutely right.* (I believe more and more in the infallibility of my thought with respect to myself, and this is too fair. Nonetheless, with this thoughtwriting, where one is at the mercy of the first outside distraction, “ebullutions” can occur. It would be inexcusable for us to pretend otherwise. By definition, thought is strong, and incapable of catching itself in error. The blame for these obvious weaknesses must be placed on suggestions that come to it from without.) It is, in fact, difficult to appreciate fairly the various elements present: one may even go so far as to say that it is impossible to appreciate them at a first reading. To you who write, these elements are, on the surface, as strange to you as they are to anyone else, and naturally you are wary of them. Poetically speaking, what strikes you about them above all is their extreme degree of immediate absurdity, the quality of this absurdity, upon closer scrutiny, being to give way to everything admissible, everything legitimate in the world: the disclosure of a certain number of properties and of facts no less objective, in

the final analysis, than the others.

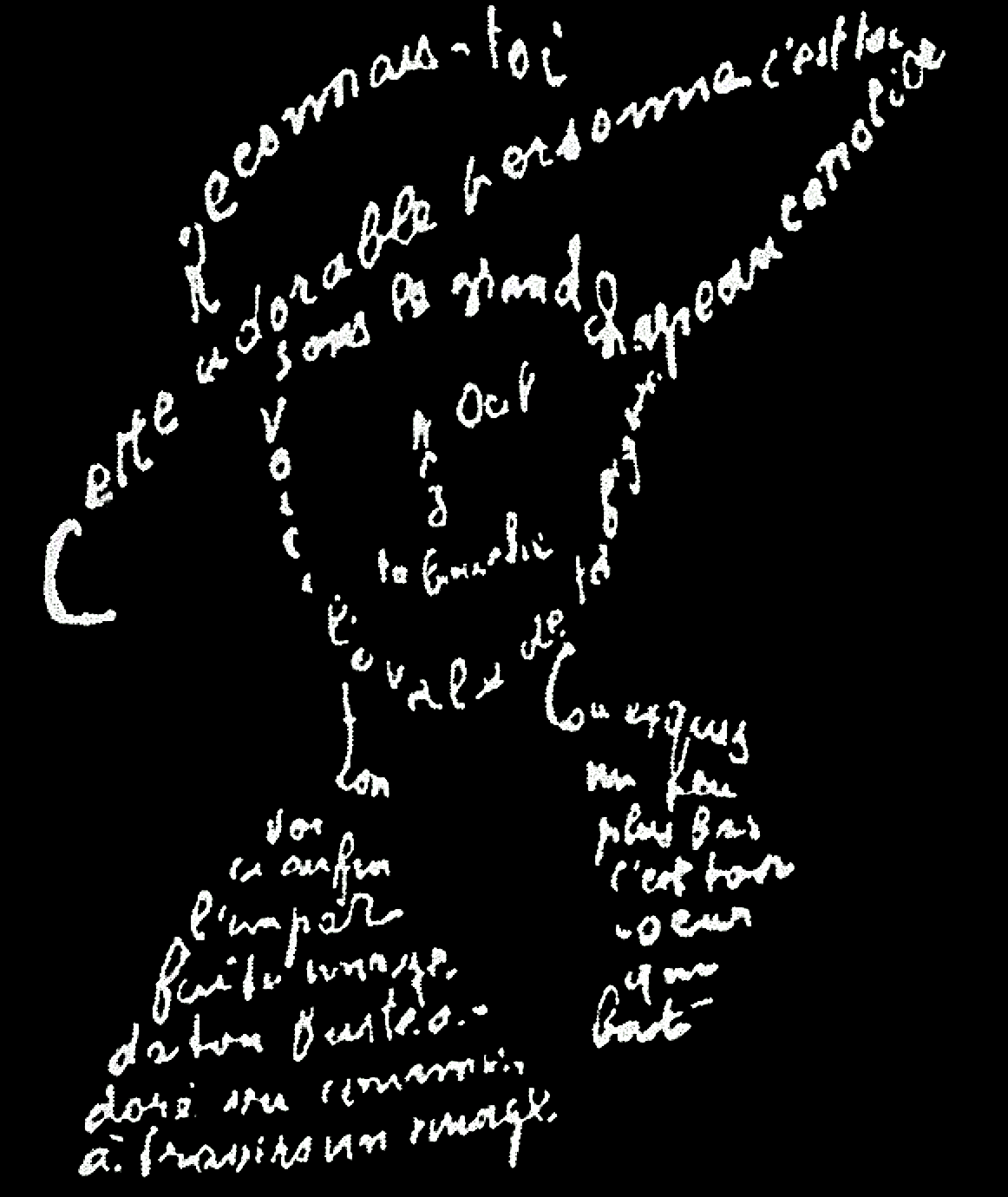

Caligram by Apollinaire

Caligram by Apollinaire

In homage to Guillaume Apollinaire, who had just died and who, on several occasions, seemed to us to have followed a discipline of this kind, without however having sacrificed to it any mediocre literary means, Soupault and I baptized the new mode of pure expression which we had at our disposal and which we wished to pass on to our friends, by the name of SURREALISM.[. . .]

Those who might dispute our right to employ the term SURREALISM in the very special sense that we understand it are being extremely dishonest, for there can be no doubt that this word had no

currency before we came along. Therefore, I am defining it once and for all:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner — the actual functioning of thought.

Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

ENCYCLOPEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of

thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life. [. . .]

. . .The mind which plunges into Surrealism relives with glowing excitement the best part of its childhood. For such a mind, it is similar to the certainty with which a person who is drowning reviews

once more, in the space of less than a second, all the insurmountable moments of his life. Some may say to me that the parallel is not very encouraging. But I have no intention of encouraging those who tell me that. From childhood memories, and from a few others, there emanates a sentiment of being unintegrated, and then later of having gone astray, which I hold to be the most fertile that exists. It is perhaps childhood that comes closest to one’s “real life”; childhood beyond which man has at his disposal, aside from his laissez-passer, only a few complimentary tickets; childhood where everything nevertheless conspires to bring about the effective, risk-free possession of oneself. Thanks to Surrealism, it seems that opportunity knocks a second time. It is as though we were still running toward our salvation, or our perdition. In the shadow we again see a precious terror. Thank God, it’s still only Purgatory. With a shudder, we cross what the occultists call dangerous territory. In my wake I raise up monsters that are lying in wait; they are not yet too ill-disposed toward me, and I am not lost, since I fear them. [. . .]

Surrealism, such as I conceive of it, asserts our complete nonconformism clearly enough so that there can be no question of translating it, at the trial of the real world, as evidence for the defense. It could, on the contrary, only serve to justify the complete state of distraction which we hope to achieve here below.

Kant’s absentmindedness regarding women, Pasteur’s absentmindedness about “grapes,” Curie’s absentmindedness with respect to vehicles, are in this regard profoundly symptomatic. This world is only

very relatively in tune with thought, and incidents of this kind are only the most obvious episodes of a war in which I am proud to be participating. Surrealism is the “invisible ray” which will one day enable us to win out over our opponents. “You are no longer trembling, carcass.” This summer the roses are blue; the wood is of glass. The earth, draped in its verdant cloak, makes as little impression upon me as a ghost. It is living and ceasing to live which are imaginary solutions. Existence is elsewhere.

André Breton. Excerpt from the First Manifesto of Surrealism in Art in Theory 19001990:

An Anthology of Changing Ideas.

Charles Harrison & Paul Wood, eds. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1992), pp. 87‐88.

Complete Text available as PDF

Luis Buñuel: Eternal Surrealist

by

Adrian Martin

How many times, in cultural history, has surrealism been declared out for the count? For the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, writing in 1929, surveying the surrealist literature of André Breton, Robert Desnos, and Louis Aragon, the glory days of this predominantly French movement—which had started scarcely a decade earlier, in 1917—were pretty much already over. Thirty years after Benjamin’s pronouncement, the troublemakers of the Situationist International, led by Guy Debord, never missed a chance to mock what they perceived as the nearly extinct dinosaur of surrealism, with its aging spokesmen no longer so terribly shocking in their studied provocations. In that same period of the ’50s and well beyond, Salvador Dalí’s clownish embrace of magazine advertising, TV, and general media celebrity hastened the impression, in many people’s minds, that surrealism was a spent force, reduced to a bunch of tired clichés—just another ephemeral art-world or showbiz fad.

But there has always been an unbeatable counterargument to any prognosis of surrealism’s demise, and it can be summed up in a name: Spanish-born Luis Buñuel (1900–1983). From his first short, the classic Un chien andalou (1929), to his final feature, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), Buñuel always stayed true to those primary surrealist principles with which he most identified: a spirit of revolt; the subversive power of passionate love, both romantic and erotic; a belief in the creativity of the unconscious (dreams and fantasies); a pronounced taste for black humor; and, last but never least, an abiding contempt for institutional religion and its representatives.

Indeed, if there is one motif above all others that characterizes Buñuel’s cinema, it is surely the parade (again, from first film to last) of nuns, priests, and even saints, presented as figures who are variously silly, pompous, repressive, and sinister—sometimes all of those attributes at once.

In any decent reckoning with Buñuel, cinema, and surrealism, we must take into account not only his own dazzling career spanning half a century, but also the profound marks it has left on the sensibility of subsequent major filmmakers. Figures including Pedro Almodóvar, Walerian Borowczyk, David Lynch, Věra Chytilová, David Cronenberg, Jan Švankmajer, Sara Driver, Arturo Ripstein, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Jean-Claude Brisseau, and Raúl Ruiz have all absorbed different aspects of the Master and reinterpreted his method in their own fashion.

However, after so many appropriations and recyclings, we may today have a somewhat skewed notion of Buñuel and his art. When we revisit his work, we discover not a torrid, psychedelic, violently disjointed style—the type of thing young art students always imagine surrealism to have been in its anarchic heyday—but the exact opposite: an unnerving calmness, a directness and simplicity in the way he staged the most outrageous situations and spun the most outlandish tales.

“Buñuel meticulously shaped his films as arrows designed to burrow straight into the unconscious of spectators, without undue filters or explanations.”

He aimed, throughout his life, for an ever less adorned manner: little musical underlining (when he does use music, it is always powerful); an extremely controlled direction of actors (he collaborated with many great ones, from Fernando Rey to Catherine Deneuve), with special attention paid to gesture and outward appearance; no facile camera tricks or ostentatious displays of color or design. Buñuel meticulously shaped his films as arrows designed to burrow straight into the unconscious of spectators, without undue filters or explanations.

According to legendary Swiss critic and programmer Freddy Buache (1924–2019), friend of Buñuel and author of an important 1970 book on him: “The true originality of Buñuel’s cinema is that it slips into the mould of the most cliché-ridden type of filmmaking, and then destroys it by bursting out from within.” This was already true even in his wildest days of youth. Un chien andalou and L’âge d’or (1930) are full of provocative, startling images (some of them devised by Dalí) that play simultaneously on the registers of black comedy (dead animals in the former) and scandalous liberation (love scenes in the latter). But Buñuel almost always begins his scenes with a perfectly composed, elegant picture of bourgeois respectability and refinement—which he then proceeds to dismantle. Across his career, the outright iconoclasm of this procedure softens—but, with a supreme sense of perversity, the uncanny sense of something not quite right comes to inhabit every situation at its outset, and in its core.

Buñuel reflected, in the course of a 1965 interview, on the need he felt to evolve beyond that first, openly antagonistic phase of surrealism. The horrors of twentieth-century history had, in his opinion, rendered the art movement’s celebrated shock tactics redundant: “How is it possible to shock after the Nazi mass murders and the atom bombs dropped on Japan?” But he went on to suggest: “One has to modify one’s method of attack, although one’s aims remain essentially the same—for the moral oppression has remained unchanged, it has simply assumed another disguise. What I’m aiming to do in my films is to disturb people and destroy the rules of a kind of conformism that wants everyone to think they are living in the best of all possible worlds.”

L’âge d’or was a movie that in its day—and as movie lore has often recounted—prompted outraged spectators (especially those affiliated with far-right political groups) to riot and tear up the cinema in which it was screening. André Breton, surrealism’s chief spokesperson at the time, celebrated the “violent liberation” that the film heralded, and its ultimate message of “a better life” whose cornerstone is “LOVE” (the capitals are his). But Buñuel, while never becoming disenchanted with such a fine surrealist credo, saw ruefully that this better life never truly came into existence for the majority of people anywhere in the world, despite the best efforts of a few feverishly intoxicated, creative imaginations. The essential stumbling block, he realized, was that deluded fantasy, held by most citizens, of existing “in the best of all possible worlds.” It’s that perception, that internalized ideology, that needed to be eroded by the powers of art—but it could only be done slowly and surely, slyly. So, as his style became more direct, his profound “message” became more indirect—and yet more pervasive in its effect on viewers, a seduction and a slap contained in the same gesture.

Buñuel’s trajectory can seem to us, in retrospect, like a starry one—few filmographies can boast the level of sustained achievement that takes us from the veritable surrealist manifesto of L’âge d’or to the corrosive social satire of Viridiana (1961) and, for his penultimate work, the completely free “sketch comedy” of The Phantom of Liberty (1974). Yet he did not always find it easy to maintain the momentum of this career. Fifteen years separate the disquieting documentary Land Without Bread (1932) from his first assignment in Mexico (where he resettled), Gran Casino. Despite the international triumph in 1950 of Los olivdados, a blending of surrealism with neorealism, Buñuel’s time as a director-for-hire in the Mexican industry cast a shadow of decline over his artistry.

As always, Buñuel was candid about his fortunes and misfortunes. Of the musicals, westerns, thrillers, melodramas, and romances he made during the 1950s, he admitted there were “three or four frankly bad films,” but nonetheless insisted: “I never infringed my moral code.” In retrospect, cinema critics and historians see the output of those years in a more positive light. For what Buñuel learned then was how to bring his surrealist impulses within the limits of traditional genre and narrative.

Throughout the 1950s and into the early ’60s, Buñuel also offers an early example, par excellence, of what we today call the transnational filmmaker. By 1950 he had already accumulated production experiences in Spain, France, Mexico, and even the U.S., squirreled away doing odd jobs in various Hollywood studios. Robinson Crusoe (1954) and Death in the Garden (1956) are both examples of coproduction (of Mexico with, respectively, the U.S. and France), allowing Buñuel to work with actors including Dan O’Herlihy and Simone Signoret—not to mention Michel Piccoli, who would reappear in his later projects. Both these films place their characters in natural surroundings (island, forest) and pitilessly weigh up so-called civilized ethics (in all its racism and paternalism) against fleeting, precarious experiences of freedom and self-knowledge.

The opening years of the 1960s must have been a puzzling time for Buñuel. On the one hand, still based largely in Mexico, he makes two of his greatest masterpieces, Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel (1962). These films have lost none of their explosive energy or dark wit. Viridiana is the most perfect formulation of a story Buñuel loved to often tell: of a deluded person (Silvia Pinal as the titular heroine) who thinks she is propagating “saintly,” Christian goodness, all the while triggering social catastrophe around her, and herself slipping into the darkest, amoral waters. The Exterminating Angel, a project Buñuel had nurtured since the mid ’50s, is a surrealistic mind-game crossed with a situation recalling Jean-Paul Sartre’s hellish No Exit: a large party finds itself inexplicably trapped inside a room, unable to simply walk out.

Yet these films bore little relation to the nouvelle vague in France or other burgeoning “new cinema” movements around the world in that era. Buñuel still had his firm fans (including the great Mexican essayist and poet Octavio Paz) but he was, in a superficial sense at least, no longer “fashionable.” By the time he made his own first fully French production, Diary of a Chambermaid, in 1964 with Piccoli and Jeanne Moreau, he found himself dismissed by the likes of Éric Rohmer in Cahiers du cinéma, painted as an artist who was repetitively and wearily settling old scores from forty years previously. It remains his most underrated film, veritably seething under its placid exterior.

In 1965, the forty-five-minute Simon of the Desert—another of his blasphemous, antireligious comedies, setting the code of ascetic denial against an array of delicious, earthly pleasures—seemed to some at the time like a characteristic postscript to a distinguished career. (Another faithful devotee, Brazilian Glauber Rocha, can be glimpsed among the wild rockers in its final scene.) But, as things happily turned out, Buñuel was on the cusp of a startling renaissance. Partly due to a sympathetic producer (Serge Silberman) and screenwriting collaborator (Jean-Claude Carrière), Buñuel relaunched his career—at the age of sixty-seven!—with Belle de jour (1967). This portrait of a demure housewife (Deneuve) who becomes a high-grade, much sought-after prostitute in the daytime effortlessly blurs the line between fantasy and reality, myth and mundanity. For the subsequent decade, it was one wonderful film after another for Buñuel, made mostly in France—with a crucial trip back to Spain for Tristana (1970), again starring Deneuve, a downbeat, antipatriarchal parable that is, at heart, his angriest and bleakest testament.

In truth, it wasn’t as if Buñuel in the later ’60s had really changed either his style or his content. Just as he remained true to surrealism, he also doggedly stuck to the inspiring, subversive literature he adored in his youth and long planned to adapt: novels by Octave Mirbeau (Diary of a Chambermaid), Benito Pérez Galdós (Tristana), and Pierre Loüys (The Woman and the Puppet, the source for both That Obscure Object of Desire, and Josef von Sternberg’s The Devil Is a Woman in 1935). But, starting with Belle de jour, there was a productive friction between the mannered surfaces of French high society and the filmmaker’s ironic sensibility that generated new sparks—and certainly won him a new, international audience.

The Milky Way (1969)—yet another satirical attack on religion and its myths—announced the tendency, prominent in Buñuel’s final decade of productivity, to use episodic narrative structures. Anecdotes, dreams, and flashbacks are cleverly strung together along some “spine” of a basic situation. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)—in which a bunch of refined characters forever tramp around looking for a good, uninterrupted meal—reverses the shut-in premise of The Exterminating Angel. In either case, the result is the same: a slow descent into uncivilized savagery, a surrender to animalistic drives, a gradual stripping away of every social hypocrisy. And, meanwhile, the wider world is overrun not by righteous revolutionaries but increasingly fanatical, insane, murderous terrorists (and, in this, Buñuel was frighteningly prescient).

The Phantom of Liberty furthered this sardonic operation of de-culturation: in one of its episodes, elegant citizens gather together at a table to defecate, and retire to their atomized bathroom cubicles in order to greedily devour food. That Obscure Object concludes with a mysterious terrorist blast that caps off, with an appropriately apocalyptic flourish, a withering comedy of manners about the non-communication between modern women (the heroine is played—not that every first-time viewer notices this—by two alternating actors, Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina) and old-fashioned men (incarnated once more by Fernando Rey). That was also the end of Buñuel’s screen career. He did nurture subsequent film projects, but decided to concentrate—with Carrière’s close assistance—on the composition of his marvelous autobiography, My Last Sigh (1982). One of its many delights is the revelation of the “ordinary,” even conservative Buñuel—the faithful husband and devoted father, the guy who even enjoys talking to exceptionally smart and enlightened priests—right alongside the forever enraged and passionate surrealist. The line everyone quotes from this book remains its best and greatest paradox: “Still an atheist . . . thank God!”

“Buñuel was a unique mixture of pure artistic intuition and the most skilled filmmaking craft—so skilled that he was able to keep making films well into the 1970s.”

Buñuel was a firm believer in the power of the unconscious mind—Carrière tells the tale of how working in tandem with the director was often a matter of spontaneously exercising the “muscle” of their imaginations—but he disallowed everything that locked unconsciousness down to something systematic and static. Buñuel was a unique mixture of pure artistic intuition and the most skilled filmmaking craft—so skilled that he was able to keep making films well into the 1970s, even as his eyesight was failing him. Buache summed up both Buñuel’s personality and his approach to filmmaking perfectly: “The artist in him cannot be separated from the man. He walks, laughs, and has a drink with friends in just the same way as he conceives a scene, shoots it, and then fits it organically into his storyline.”

He tended to laugh at critical interpretations of his work. Although, as a surrealist, he was no stranger to the Freudian tenets of psychoanalysis, he especially mocked ultra-rational attempts to rigidly decipher the “symbolism” of his images and scenes. Spiders, ants, endless roads, as well as all strange, off-screen sounds of drums, machine gun fire, or buzzing insects . . . these recurrent elements all resonated in the dramatic or comic context Buñuel gave them, but they didn’t “mean” anything exact. As a true and eternal surrealist, Buñuel believed in the poetic—not divine—mystery inherent in all things.

Adrian Martin is an Australian-born film critic based in Spain; his website, covering forty years of writing, is at filmcritic.com.au.